Michael Philip Harris (1939-2023)

Written by Mark Tasker

On December 17th, 2023, the world lost one of its great seabird ornithologists when Mike Harris died aged 84. Mike was a founder member of The Pacific Seabird Group and received its Lifetime Achievement Award in 2007. His name is forever linked to Atlantic Puffins Fratercula arctica, but his work extended to many other seabirds and into understanding their place in the marine environment.

Mike was born on April 28th, 1939, in Swansea, where he also went to school and university to gain both his BSc and PhD. A DSc followed in the late 1980s, with a later honorary professorship from Glasgow University. His Doctorate was obtained from a study of the biology of gulls on the Welsh island of Skomer.

Mike’s external PhD examiner was David Lack, who was then Director of the Edward Grey Institute at Oxford University, who offered him a post-Doctorate position working on gulls, Manx Shearwaters Puffinus puffinus and Eurasian Oystercatchers Haemotopus ostralegus on Skokholm Island, partly to follow up on the 1930s work of the pioneering seabird ornithologist, Ronald Lockley. A further post-doctoral study took Mike to the Galápagos Islands in the 1960s, primarily to study three species of storm-petrels, but also the biology of Waved Albatross Phoebastria irrorata, Flightless Cormorants Nannopterum harrisi, and tropicbirds. He even found time to collect Spirorbis polychaetes as he travelled around the islands—which led to the identification of six new species. Mike wrote the first Field Guide to the Birds of Galápagos, still one of the best guides available. He also met the tourism pioneer Lars-Eric Lindblad and was funded by him to develop a strategy for sustainable tourism for the archipelago. The legacy of that strategy still persists as anyone who has had the privilege to visit those islands will have experienced, with cruise vessels only being allowed specific time slots to visit each island in order to avoid too many visitors in any one place at any one time. Mike was also a naturalist guide on some of the pioneering cruises to Antarctica.

On returning from the Galápagos in 1972, he was appointed to a Nature Conservancy (a UK government body) job investigating the decline of UK Atlantic Puffins. This brought Mike to Scotland where he joined the then research station just outside Banchory, near Aberdeen. Puffin research took him to the remote western Scottish island archipelago of St Kilda where study plots were established on Dun—with access via a breeches buoy cable system from the main island of Hirta. We can be certain that this method would not have survived any safety inspection, but it worked well. At more or less the same time, Mike started work on the Atlantic Puffins of the Isle of May, a much more accessible island off the east coast of Scotland.

The work on the puffins rather contradicted the concept of a declining population—he found no evidence of decline on St Kilda, and much evidence of an increase on the Isle of May. In 1974, Mike surveyed the seabirds of Shetland to the north of Scotland and laid the foundations for seabird monitoring that has continued there ever since.

Mike’s work on the Isle of May Atlantic Puffins focussed initially on understanding demography and diet, which entailed much ringing of adults, collection of food loads dropped under nets, and watching food deliveries to burrows. This work culminated in his 1984 book, The Puffin, that summarized all knowledge on the species (and related species) to that point. In subsequent years, Mike set out to answer many of the questions raised in that book—for instance, where do Atlantic Puffins spend the winter (geolocators indicate most Isle of May birds remain in the north-western North Sea, but some venture to the eastern Atlantic). In the early 1980s, he started to take an interest in the biology of other seabirds breeding on the Isle of May, such as Black legged Kittiwakes Rissa tridactyla and European Shags Gulosus aristotelis, but most especially Common Guillemots (Common Murres) Uria aalge. The early 1980s also marked another important transition in his life, the start of work with Sarah Wanless, who not only became his most important co-researcher but he subsequently also married. The dynamic partnership with Sarah led to a substantial increase in research publication and wider influence on seabird studies. In the mid-1980s, he was key in designing and setting up the UK and Ireland Seabird Monitoring Programme, the results of which have proved important in understanding trends in seabird populations and in the effects of over-fishing of sandeels (sand-lance) Ammodytes within the feeding range of Scottish seabird colonies. A new and much expanded and rewritten edition of The Puffin book, co-authored with Sarah, was published in 2011.

Mike’s links with the Pacific continued after his work in the Galápagos. He had visited Hawai‘i while on the Galápagos, and memorably managed to get altitude sickness! His first (known) PSG meeting was in Asilomar in 1982, a tour of colleagues and their work in Alaska followed in 1985. Memories of that visit included a stay on St George Island in the Pribilofs where Sarah and Mike were present when the first ever download of a time-depth recorder from a sea lion occurred—a harbinger of future remote instrumentation on seabirds that both Sarah and Mike engaged in. Mike also marveled at how Vernon Byrd and his team coped with the logistical challenges of monitoring local seabird populations. The weather was atrocious, and Mike never did see the main breeding areas on the High Bluffs because of the dense fog!

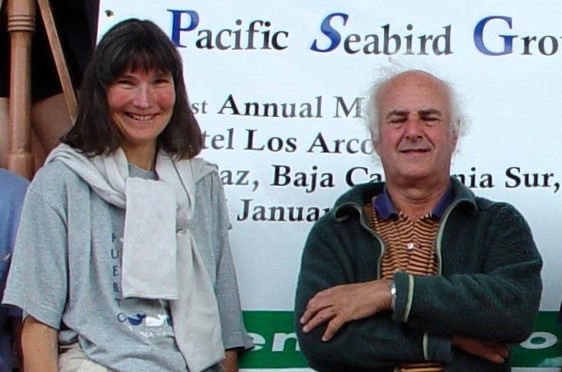

In 1995, Mike and I travelled to Alaska as part of the review of the consequences on the Exxon Valdez oil spill. In 2004, Sarah was one of the plenary speakers at the PSG meeting in La Paz, Baja California and Mike was immensely proud to receive the most supportive spouse award from George Divoky at that meeting!

In another link to the Pacific, one of the most exciting moments of Mike’s time on the Isle of May was when Yutaka Watanuki, visiting from Japan, downloaded the first data from miniature digital cameras attached to European Shags showing birds foraging for sandeels (sand lance).

On a UK and global basis, there are very many seabird researchers who owe their careers and quality of research to Mike’s influence. This was recognised formally, along with the PSG Award, with the award of the British Ornithologists’ Union’s Godman-Salvin medal in 2006 and the Seabird Group’s Lifetime Achievement Award in 2016. Mike has written or co-authored more than 300 publications; research that has been cited more than 15,000 times—more publications are in the pipeline and his thinking will last many years into the future.

Mike’s style was of great informality, but with deep practicality and discipline. This made him a very good mentor, easy to approach, and always generous with his time. He loved fieldwork, and his attention to detail, especially when observing seabirds led to many great insights. His observation that the degree of parental care was a key indicator of the health of Common Guillemot (Common Murre) colonies has led to considerable insights into the effects of climate change on seabirds. The data to show this was collected over four decades of very careful observation of Guillemot behavior.

Mike understood the importance of working with and being part of a community, especially on a small island. Mike made a difference to the seabirds and to the islands he loved and to the many people whose lives were changed for the better by knowing him. Our sympathies to all those who knew him, but particularly to Sarah.