King Eider migration in the Chukchi Sea — July 23–25, 2023

Mark Rauzon, Seabird Observer, USFWS volunteer (mjrauz@aol.com)

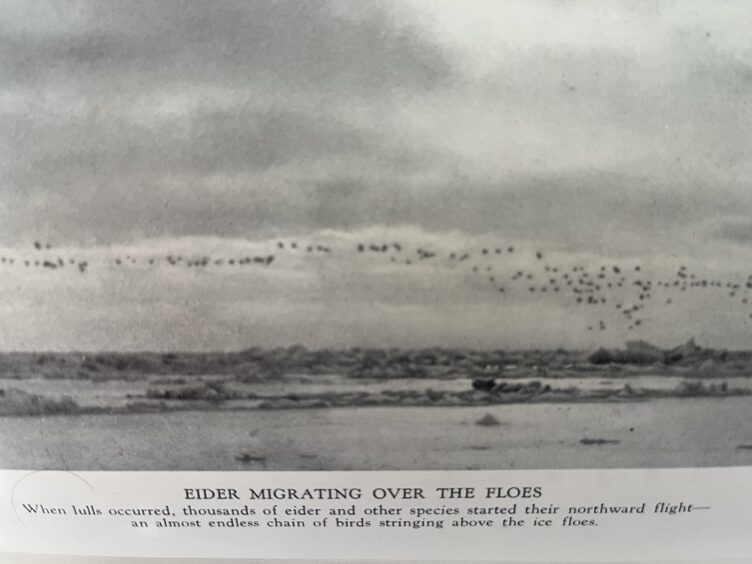

As the Canadian Coast Guard icebreaker CCGS Sir Wilfred Laurier moved to our last station, DBO5-2, where we sampled at the edge of Barrow Canyon, a deep channel into the Arctic Ocean, I began to see male king eiders (Somateria spectabilis) moving south in long migrating flocks, as literally thousands flew south in hundred-bird skeins. They were not close (they know the reach of a rifle), but we were able to see them on radar going eight knots south 2.9 miles out. Seeing them reminded me of the historical recounts of early ornithologists seeing vast eider flocks amidst the ice pack. Alfred Bailey’s monograph, Birds of Arctic Alaska, published in 1948 by the Colorado Museum of Natural History, stimulated my keen interest in 1975 when I picked up the book at a remainder sale for five dollars, and 48 years later, got to have a similar experience. Despite the diminishment of Arctic species, here was a time-honored spectacle still echoing the past glories, like a living bio-diorama. Bailey writes: “The handsome King Eider were exceedingly numerous along the north coast of Alaska during migration in 1922…. Hersey gives an excellent account of the fall migration on males leaving the breeding grounds. His ship was caught in the ice off Wainwright from August 10 to 20 and during those days migrating flocks of King Eiders were constantly passing. They were in flocks of from 75 to 300 following the shoreline but keeping at least a mile from land. During his ten days of observation ‘there appeared to be no diminution in the number of birds coming out of the north.”

In The Birds of Alaska, the 1959 field workers bible, Ira Gabrielson and Fredrick Lincoln write: “The migration along the shores of the Bering Sea and Arctic coast is remarkably spectacular. We see them first two miles away. A twisting, shimmering line of birds flying close to the water, miraged in such a manner that each bird seems to be connected by an elastic string to its reflection in the water. As they rise and fall in their flight, this elastic string seems to lengthen and shorten and grow narrower and wider. The effect of a thousand birds so seen almost makes one believe he is ‘seein’ things…”

I felt a connection to these past field biologists — a mute pride in the privilege in seeing what they saw a century ago still impressively flying at the ice edge. Bailey put it subtly: “The sight of long strings of fast-moving eiders of four species, murres, puffins, cormorants, and gulls in seemingly endless chains is one of the memories of a field man’s experience on Bering Strait.”