Assessing the risk: identifying seabirds and seals most at risk from climate change

By Milan Sojitra (milan.sojitra@utas.edu.au), Stuart Corney (stuart.corney@utas.edu.au), Mark Hemer (mark.hemer@csiro.au), Sheryl Hamilton (sheryl.hamilton@nre.tas.gov.au), Julie McInnes (julie.mcinnes@utas.edu.au), Sam Thalmann (sam.thalmann@nre.tas.gov.au) & Mary-Anne Lea (maryanne.lea@utas.edu.au)

Marine predators such as seabirds and seals are facing unprecedented threats due to climate change. These animals are especially vulnerable during their breeding seasons, when their young are most vulnerable to predation, diseases, extreme weather, etc. The unique dual dependency of these predators—breeding on land but relying on the ocean for food—makes them susceptible to changes in both habitats. Understanding which species are most at risk and identifying the specific threats they face is crucial for prioritising conservation efforts and efficiently allocating limited resources.

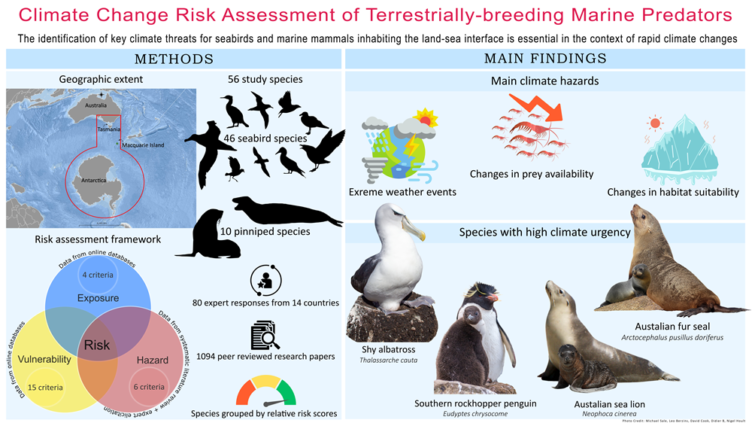

Our research offers a comprehensive climate risk assessment for 53 marine predator species, including 43 seabird and 10 pinniped species, across southeast Australia, subantarctic Macquarie Island, and Antarctica. Using this new trait-based climate risk assessment framework, we identify the species most vulnerable to climate change, especially during breeding season. This research provides guidance for conservation organisations to prioritise their efforts based on specific threats for given species.

What are the main threats?

Our research highlights extreme weather events as the most significant threat, negatively affecting 36 of the studied species. The most frequent events include snowstorms, heavy rain, strong winds, floods, storm surges, and heatwaves. Longer-term shifts in habitat suitability and prey availability driven by climate change were also significant threats, affecting 23 species. These environmental changes threaten not only immediate survival of seabirds and seals but also their long-term population trends and demography.

What are the most vulnerable species?

Among seabirds, the species identified with highest climate urgency include the Shy Albatross (Thalassarche cauta) and Southern Rockhopper Penguins (Eudyptes chrysocome). Their high risk status is due to a combination of their life history traits, ecological requirements, and the direct effects of climate change on their breeding success and survival.

Shy Albatross breed exclusively on three remote islands in Tasmania with limited at-sea distribution during the breeding season. The threats they face are mostly extreme weather events along with occasional tick-borne disease outbreaks, and competition with Australasian Gannets (Morus serrator) at one of the breeding colonies. Southern Rockhopper Penguins, however, are primarily threatened by longer-term changes in climate, leading to poor body conditions, reduced reproductive investment, and high adult mortality. Extreme rainfall events occasionally result in significant breeding failures for these penguins.

The growing threat of extreme weather

Recently, the world experienced its hottest single day on record, a 50°C temperature anomaly in Antarctica, severe heatwaves in Europe, and catastrophic floods across the Americas, Africa, and Asia. These extreme weather events are stark reminders of the accelerating pace of climate change and its far-reaching consequences.

Like human systems, marine predators are also vulnerable to such extreme occurrences with significant breeding failures recorded worldwide. The latest IPCC AR6 report predicts a heightened frequency and increased severity of extreme weather events, suggesting that their ecological impacts on marine predator populations will become increasingly prominent and concerning in the future. For instance, Shy Albatross chick mortality increases significantly during extreme or persistent heatwaves (1), Adélie Penguins (Pygoscelis adeliae) in Antarctica have faced complete breeding failures due to unusual rain events and changes in sea-ice (2), and severe snowstorms have caused breeding failures for many Antarctic seabirds (3). Marine heatwaves also slow chick growth and cause reduced breeding success for Common Diving-Petrels (Pelecanoides urinatrix) and Fairy Prions (Pachyptila turtur) in Bass Strait (4).

Conservation Implications

Our findings indicate that certain groups of marine predators, including albatrosses, penguins, and eared seals, are particularly vulnerable to climate change. Studied species that breed in lower latitudes, such as those on temperate habitats and subantarctic islands, are at greater risk compared to those breeding in Antarctica. This pattern suggests that conservation efforts should prioritise for species in these regions, where the impacts of climate change are more pronounced and immediate.

Protecting critical breeding habitats is essential, as is implementing fine-scale monitoring protocols to detect and respond promptly to emerging threats. Developing threat-specific climate adaptation strategies is crucial. For instance, measures could include enhancing breeding habitats by promoting native vegetation, supplementing artificial nests to protect against extreme elements, or even translocating species to more suitable environments if their current habitats become untenable.

Conservation efforts are often more feasible on breeding grounds than across vast oceanic habitats, making these areas a focal point for intervention. However, protecting breeding sites alone is not sufficient, comprehensive strategies must also address the broader environmental changes affecting these species throughout their life cycles, including during migration and foraging at sea. Tackling climate change effectively will require international cooperation to implement global emission reductions, protect critical habitats, and coordinate conservation strategies across national boundaries.

Collaborative efforts for future research

Protecting at-risk species will require a collaborative approach between policymakers, industry and the blue economy, along with scientists and conservation managers. By identifying the species most at risk and understanding the specific threats they face, our research provides a roadmap for targeted conservation efforts. Engaging with stakeholders from various sectors is critical to developing and implementing effective conservation strategies that can address the complex challenges posed by climate change.

Our findings also highlight the need for further research, particularly on at-risk species as well as lesser-studied species and climate hazards. As the impacts of climate change continue to intensify, it is crucial to address knowledge gaps and revisit this assessment in future. Ultimately, safeguarding these species and their ecosystems in an era of unprecedented environmental change will depend on our collective ability to act swiftly, decisively, and collaboratively.

For a deeper dive into our findings, you can read the full paper (5): Sojitra et al. 2024. Traversing the land-sea interface: A climate change risk assessment of terrestrially breeding marine predators.

References

1. Mason, C., A.J. Hobday, R. Alderman, and M.A. Lea, Shy albatross Thalassarche cauta chick mortality and heat stress in a temperate climate. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 2024. 737: p. 137-145 DOI: 10.3354/meps14494.

2. Ropert-Coudert, Y., A. Kato, K. Shiomi, C. Barbraud, F. Angelier, K. Delord, T. Poupart, P. Koubbi, and T. Raclot, Two Recent Massive Breeding Failures in an Adelie Penguin Colony Call for the Creation of a Marine Protected Area in D’Urville Sea/Mertz. Frontiers in Marine Science, 2018. 5: p. 264 DOI: 10.3389/fmars.2018.00264.

3. Descamps, S., S. Hudson, J. Sulich, E. Wakefield, D. Gremillet, A. Carravieri, S. Orskaug, and H. Steen, Extreme snowstorms lead to large-scale seabird breeding failures in Antarctica. Current Biology, 2023. 33(5): p. R176-R177 DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2022.12.055.

4. Eizenberg, Y.H., A. Fromant, A. Lec’hvien, and J.P.Y. Arnould, Contrasting impacts of environmental variability on the breeding biology of two sympatric small procellariiform seabirds in south-eastern Australia. PLoS One, 2021. 16(9): p. e0250916 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250916.

5. Sojitra, M., S. Corney, M. Hemer, S. Hamilton, J. McInnes, S. Thalmann, and M.A. Lea, Traversing the land-sea interface: A climate change risk assessment of terrestrially breeding marine predators. Global Change Biology, 2024. 30(8): p. e17452 DOI: 10.1111/gcb.17452.