Ten years of monitoring endangered ʻuaʻu in protected reserves on east Maui

By Jenni Learned (learnedj@hawaii.edu) and Jay Penniman (jayfp@hawaii.edu)

Before humans were established in the Hawaiian archipelago, ʻuaʻu (Pterodroma sandwichensis; Hawaiian Petrel) were among the most numerous of bird species in the islands (1). Today, remnant breeding populations are restricted to remote and primarily high elevation habitats. Various conservation agencies manage breeding assemblages on Kauaʻi, Lānaʻi, Maui, and Hawaiʻi islands. Acoustic monitoring has detected ʻuaʻu on Oʻahu and Molokai; however, breeding burrows have yet to be identified (2). The largest remaining population of ʻuaʻu exists on Maui within the summit district of Haleakalā National Park and expands into neighboring parcels on leeward and windward slopes. At the Maui Nui Seabird Recovery Project (MNSRP), we monitor and protect ʻuaʻu in the upper Nakula Natural Area Reserve and Kahikinui Forest Reserve on the leeward slopes of Haleakalā.

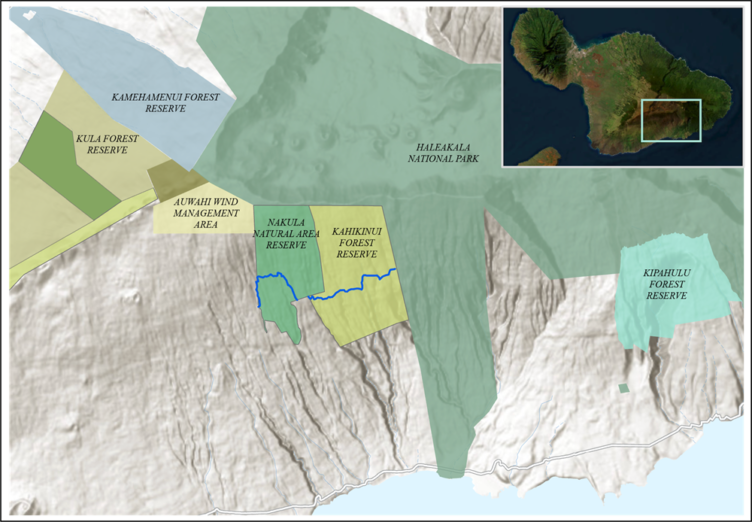

Haleakalā is a massive dormant volcano and the dominant topographical feature of east Maui. On the arid leeward slopes, habitat ranges from alpine rockland above 2400 meters to subalpine shrubland, grassland, and tropical dry forest at lower elevations. Surficial geology is primarily rocky with intermittent cinder fields. The average grade is around 30% and the slope is transected by steep-sided gulches. Despite the rugged topography and harsh environmental conditions, introduced mammalian predators (cats, mongooses, rodents, and pigs) are widespread and pose a significant threat to indigenous avifauna and bats. Introduced grazing mammals including cattle, goats, and deer cause severe habitat degradation and landscape alteration. To counteract these threats, Haleakalā National Park maintains programs to remove predators and to protect and restore habitat (3). Outside of the park, partnership agencies like MNSRP adopt similar methodology with the goal of recovering ʻuaʻu across the historic range. Hawaiʻi State Division of Forestry and Wildlife (DOFAW) completed ungulate exclusionary fencing around Nakula and Kahikinui reserves and began removing feral ungulates in 2014. MNSRP works within the fenced reserves above 2070 meters, an area of approximately 530 hectares (Figure 1).

ʻUaʻu are burrow-nesting procellariform seabirds that raise their single chick during the summer months. MNSRP monitors each identified burrow throughout the breeding season, visiting at least once per month to document activity signs (guano, feathers, collected vegetation/nest material, odor, tracks, digging) and to track entrance/egress from burrows using toothpicks erected across the entrance (Figure 2). As resources allow, we deploy motion-activated game cameras at select active burrows. Game camera data provide a complete record of ʻuaʻu activity, including timing of adult attendance, nest maintenance and other pair activities, and chick emergence and fledge date (Figure 3). Camera data also reveal predator and feral goat activity. In addition to small-mammal kill traps established across the sites, we use the camera data to deploy traps responsively to predator detections at burrows. At the conclusion of the breeding season, burrows are categorized based on status (breeding or non-breeding, if breeding; successful or failed) to estimate reproductive success. Annual phenology and reproductive success data, as well as predator detection and capture data are stored in the long-term database for the Haleakalā ʻuaʻu population.

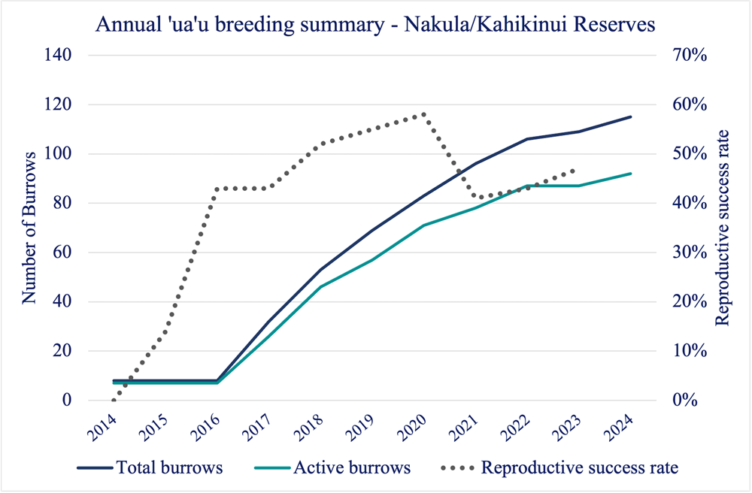

Ungulate exclusion and predator management in Nakula and Kahikinui positively impact ʻuaʻu on leeward Haleakalā. Following the completion of the fence in 2014, a thorough search of ideal habitat produced only eight active ʻuaʻu burrows. MNSRP continues to perform standardized burrow searching every year in July. After 10 years of site protection and management, the ʻuaʻu burrow count has increased to 115. On average, ʻuaʻu are establishing new burrows at a rate of 11 burrows annually. The reproductive success rate, at 0% and 14% in 2014 and 2015, now averages 48% (Figure 4).

In addition to observation data, MNSRP uses tools to assess ʻuaʻu population trends indirectly. Every three years, we deploy automated acoustic monitors (AAM) for the duration of the breeding season at 19 established sites. The acoustic data reveal spatiotemporal changes in ʻuaʻu activity across leeward Haleakalā since 2014. Bayesian analyses show a 20% annual increase in ʻuaʻu calling activity (4). More specifically, these data indicate a proportionally greater rate of increase at lower elevations, suggesting that the ʻuaʻu population could be expanding outward from the denser aggregations within Haleakalā National Park. Furthermore, in the summer of 2021, we initiated annual ornithological radar surveys at 16 sites around Maui replicating a pilot survey conducted in 2001 (5). Several sites are located downslope from the Haleakalā ʻuaʻu population, where adults can be detected as they return to their breeding burrows after sunset. While it is too early to draw precise conclusions from the long-term study, the data suggest stable if not increasing passage rates for ʻuaʻu transiting to Haleakalā.

Seabirds tend to have long lifespans, low reproductive output, and cryptic habits. They continuously adapt to changing environmental conditions impacting their marine foraging grounds and their terrestrial habitats. All of these factors make it necessary to maintain consistent long term monitoring records to assess population trends and response to management. For the ʻuaʻu on Haleakalā, early interpretation of a long-term data set suggests that dedicated work against the threats imposed by introduced species is having a positive effect. There is no doubt that protective management activities within Haleakalā National Park, ongoing for almost 50 years, have saved the Maui ʻuaʻu population from precipitous decline. The combined efforts of partnership agencies in recent decades support recovery and population growth. In just 10 years, ʻuaʻu have shown a clear and positive response to efforts in Nakula and Kahikinui. With seabirds suffering declines globally, we are hopeful that this report serves as an optimistic reference for seabird restoration across Hawaiʻi and beyond.

References

- Olson, S. L., and H. F. James. (1984) The Role of Polynesians in the Extinction of the Avifauna of the Hawaiian Islands. Quaternary Extinctions: A Prehistoric Revolution. University of Arizona Press. 769-780.

- Young, L. C., E. A. VanderWerf, M. McKown, P. Roberts, J. Schlueter, A. Vorsino, and D. Sischo. (2019) Evidence of Newell’s Shearwaters and Hawaiian Petrels on Oahu, Hawaii. The Condor: Ornithological Applications 121: 1-7.

- Kelsey, E.C., J. Adams, M. F. Czapanskiy, J. J. Felis, J. L. Yee, R. L. Kaholoaa, and C. N. Bailey. (2019) Trends in mammalian predator control trapping events intended to protect ground-nesting, endangered birds at Haleakalā National Park, Hawaiʻi: 2000–14. U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2019. https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr20191122.

- Gustafson, Z., A. Fleishman, D. C. Branco, K. Dunleavy, and M. T. Tinker. (2023) Automated acoustic surveys for Hawaiian petrel (Pterodroma sandwichensis) and Band-rumped storm petrel (Oceanodroma castro) at Kahikinui Forest Reserve on East Maui, Hawaii. Conservation Metrics, Inc.

- Cooper, B. A. and R. H. Day. (2003) Movement of the Hawaiian petrel to inland breeding sites on Maui island, Hawaiʻi. Waterbirds 26: 62-71.